writing

you are here [x]: Scarlet Star Studios > the Scarlet Letters > writing

July 14, 2013

women in animation 2013

by sven at 1:56 pm

While putting films in sequence for this year's NW Animation Fest, I was struck by the scarcity of female characters. Because gender interests me, I decided to throw together some quick statistics to study what's going on.

My data set consists of the 154 films that were selected for screening at our 2013 festival. Here's what I found:

BYLINE

(In the program, who did we list on the film's "created by" line?)

66% Male

19% Female

15% both / name of studio only

GENDER OF FILM'S PROTAGONIST

66% Male

20% Female

14% none (abstract or unidentifiable)

If we stopped there, you might guess that men exclusively make films about men, and women make films about women. But there's actually a stronger bias at work.

MALE BYLINES

72% Male protagonist

12% Female protagonist

17% abstract, or gender of protagonist is unidentifiable

FEMALE BYLINES

41% Male protagonist

48% Female protagonist

10% abstract, or gender of protagonist is unidentifiable

GROUP BYLINES

(creators of more than one gender listed, or name of studio only)

83% Male protagonist

13% Female protagonist

4% abstract, or gender of protagonist is unidentifiable

What I see here is that when women make a film, they create female protagonists about 1/2 the time. But when men make films, they create male protagonists about 3/4 the time. Group projects feature male protagonists about 4/5 the time.

It seems intuitive that artists would have a bias toward creating protagonists that look like themselves. But this is not really the case. Women seem to have a fairly egalitarian interest in both men and women. Men, in contrast, tend to take a male-identified point of view.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: nw animation festival, writing

May 26, 2013

animation interview with shelby clanton

by sven at 10:18 pm

Students sometimes write, asking me to respond to interview questions for a class assignment. Occasionally I say yes. This interview was for Shelby Clanton at Skagit Valley College in Washington state.

1. What do you think of the current state of animation?

"Animation" is an umbrella term that encompasses several methods of filmmaking whose fates are often at odds with one another.

We are at a moment in history when "traditional" hand-drawn animation is suffering and becoming more rare. Many view animating computer-rendered simulations of 3D objects as a more certain career path — and they're probably right. Hand-drawn animation depends greatly upon individual talent, whereas the ability to endlessly edit CG files appears to give studio management more freedom to swap employees in and out. Note that in recent weeks Disney has (once again) decimated its hand-drawn animation department.

Meanwhile, stop-motion animation is going through a renaissance. Multiple feature-length stop-motion films in a single year would have been unthinkable 20 years ago. The evolution of technology — digital cameras plus framegrabbing software — has made this method much more accessible than it once was. Also, in an age when nearly every image we see in the public sphere has been Photoshopped, there is something refreshing about an art form that uses real physical objects to perform its magic tricks.

Film in general is increasingly indistinguishable from animation. In most live-action films, there's not a single frame that hasn't been digitally retouched and manipulated in some way. However, Hollywood has terribly abused the special effects houses that are responsible for so many of its blockbusters' memorable moments. It was a pivotal moment at the 2013 Academy Awards this year when "The Life of Pi" was taking home the Oscar — while Rhythm & Hues (which did the effects work) was simultaneously filing for bankruptcy.

The most important thing affecting the art form right now, however, transcends animation. In 2012, celluloid film effectively came to an end. As one writer put it, every film print is now an archival print. A hundred years of film history now enters a period of physical decay, and any plans to preserve our cinematic past are haphazard at best. By the same token, films made in the digital era are only as archival as the harddrives they're stored on — which generally aren't expected to last more than 5 years. Whatever independent film you watch in 2013, ask yourself: will this film still exist in any form ten years from now?

2. Where do you think animation is going in the future?

In the realm of CG, mingling motion capture with with frame-by-frame animation is the way forward. Live action and CG characters will continue to become increasingly interchangeable and indistinguishable.

In the realm of stop-motion, LAIKA is doing the most innovative, ground-breaking work using 3D printers to generate precisely modeled objects for replacement animation.

2D animation seems to be moving along a historical path similar to that of painting. It holds a respected position as the archetype of animation — but most industry work is now entirely software-based. Just as the camera is better able than drawing to capture photo-realistic images, so too CG has laid claim to the realm of realism. Most 2D artists distinguish themselves with various forms of expressionism. Doing realistic hand-drawn work is no longer deemed an important goal, but is instead (unfairly) seen as a sort of stunt pulled off by obsessive masochists.

3. What do you think are some animation trends that people will be seeing in upcoming film releases?

Disney. Pixar. Dreamworks. LAIKA. Aardman. When you think about upcoming film releases, are these the companies you're thinking of? In the USA, Disney will continue its princess franchise. Snarky CG animals will continue to come out each summer until a few films in a row are terrible box-office bombs, or the companies collapse financially for other reasons — such as decreased revenue due to competition from Netflix, Hulu, and the like. A few major players will put out stop-motion films, at the very least keeping a foot in the game to avoid ceding complete control of the field.

More interesting, I think, are the inroads that films from other countries are beginning to make into the US. Studio Ghibli releases are now anticipated as major events. A few Polish films have made it into theatrical distribution in the US recently. With the teen-generation phenomena of K-Pop, I'm very curious to see if Korean animation will begin to gain popularity.

Animation certainly exists in the Cineplex — but there is also a whole separate culture of films that live in the festival circuit and art house cinemas. In these independent channels, what's most exciting is to see feature-length films being released without the support of studios. Bill Plympton's "Cheatin'," Christiane Cegavske's "Blood Tea and Red String," and M dot Strange's "We are the Strange" are all recent feature-length films created essentially by a single individual, which nonetheless made it into circulation. Crowd-sourced films are also an exciting new development just emerging on the scene — particularly in the realm of CG, where software is commonly available, and models can be shared via online transfer.

4. What is your favorite style of animation?

Personally, I have a deep love for stop-motion puppet films. Story-wise, I adore an artist who can dip into fantasy, surrealism or magic realism — while simultaneously delving into subtle, carefully observed emotions on the part of the story's characters. "The Eagleman Stag" by Mikey Please and "Belly" by Julia Pott are excellent recent examples. (Both are available on Vimeo.)

posted by sven | permalink | categories: writing

August 8, 2012

truths about animation

by sven at 4:58 am

Animation is literally magic, breathing life into something inanimate.

Animation is diverse, encompassing many possible methods, media, and technologies.

Animation is a serious art form with enormous potential for creative expression.

It is possible to do things with animation that cannot be done in any other art form.

Animation is often misunderstood, being identified solely with kids, comedy and computers.

Many people enjoy mainstream animation; few have seen much independent animation.

To artists, the appeal of animation is being able to turn any daydream into an external, living, sharable vision.

Trading hours of real life for seconds of life on screen is laborious and isolating.

The amount of labor that animation requires makes it an extremely expensive art form.

To justify the effort, animators need audiences and hope for money.

Indie animation is almost entirely a genre of short films.

As with shorts in general, most films' only chance of getting sold is through compilations.

Festivals excel at compiling films for audiences.

Despite occasional screening fees, distribution deals and prizes, showing at festivals is unlikely to earn a typical animator any significant money.

Festivals provide filmmakers with an audience's human reactions to their work.

The emotional reactions of a crowd are different from those of an individual or small group.

It is easier to watch difficult films when they are interspersed with fun ones.

If audience members don't feel like they had enough fun at a festival, they won't come back.

When people return to a festival annually, it begins to feel like a kind of family reunion.

Though premised on screening films, festivals should emphasize and support the individuals endeavoring to create art.

Animators are more likely to persist and thrive when they feel connected to a supportive community.

Seeing other people's work helps inspire animators to make new films.

Anyone with a desire to animate can learn the basic principles quite quickly.

The main requirements for doing animation are enthusiasm and patience.

Emerging artists benefit from seeing a huge number of short indie films, as a way to become literate.

There is more to be learned from studying flawed films than perfect ones.

Master animators develop by continuing to make more films, experimenting and trying improve upon previous projects.

Animation evolves as an art form through a dialectic of animators making creative responses to one another's work.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: nw animation festival, writing

April 27, 2012

stopmo interview with elizabeth carmona

by sven at 2:40 am

Elizabeth Carmona, a graphic design student in El Salvador, is doing her graduation thesis research on stop-motion. She found my work via StopMotionAnimation.com and asked for an interview. I have a hard time saying no to pontificating about the subject — particularly if it might help an emerging artist — so here's what came of it...

Eliza: Thanks a lot for your answer and for agreeing to help me!

I'm doing a guide about "How to do stopmotion animation", and I was reading your site and it has such a wonderful information about the technique (I specially find really useful and interesting the essay about pros and contras of cg, and the aesthetics of stopmotion) and the way you've been experimentating with armatures.

So for the interview I wanted to ask you:

Why did you choose stop-motion?

Sven: Stop-motion is something that I've wanted to do since I was maybe 6 years old. I read books about animation and special effects because I was in love with Star Wars and films like it. But animation seemed impossible then. I just couldn't see myself shooting on film and then having to send it off for developing. In 2002, one of the books I'd read as a child — The Animation Book, by Kit Laybourne — was republished with new material about computers. Suddenly it dawned on me: all you need now to do animation is a computer — and I've already got one of those. So I started doing motion graphics and kinestasis using AfterEffects. But it still felt like something was missing. I enrolled for a hands-on class about shooting Super8, so I could say I'd at least tried using celluloid. In the process of doing that, I finally got my chance to try stop-motion. And when I did, I was hooked. It was like a fever. For at least a year, it seemed like I did nothing but study stop-motion and experiment with puppet-making materials. I could talk about the various things I love about stop-motion — how you're making real, tangible objects come to life (magic!) — but the attraction goes beyond reason. I bonded with stop-motion at a young age, and late in life am unable to shake its gravitational pull.

Who have been your influences?

I fell in love with Star Wars, King Kong, all of Ray Harryhausen's films... There's a lineage there, that goes from Willis O'Brien to Uncle Ray to Phil Tippett. But while the sci fi / fantasy stuff is ingrained in my bones, it's actually the more stylized, artsy puppet animation that I'm interested in making myself. There's another lineage: which goes from Vladislav Starevich's The Cameraman's Revenge to George Pal's Puppetoons to Henry Selick's The Nightmare Before Christmas. In the current scene, I'm most inspired by folks like Jeff Riley (Operation: Fish), Neil Burns (The Nose), Nick Hilligoss (L'Animateur), and Barry Purves (Tchaikovsky - an elegy).

From where do you take inspiration for a new story or character? what comes first for you?

I'm very interested in process. Story and character are important, but pretty much everything I've done so far has begun from wanting to tackle a specific technical challenge: such as lipsync or replacement faces. Time has also often been a consideration — challenging myself to make a film in a set number of days or weeks. I find that by starting with the limitations I want to obey, I'm less likely to get sucked into attempting a project that's too big to be completed in a tolerable amount of time.

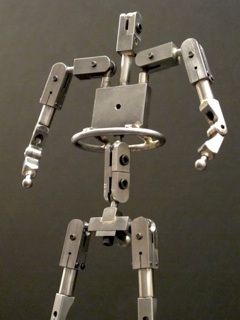

While making the puppet, what are the most important things you consider?

A puppet is only as good as its armature. To get really nuanced movement, you want to have a ball and socket armature. So I've spent a lot of time learning how to create professional-level steel armatures using a milling machine and lathe. Armatures are interesting to me as an art form unto themselves, though. Most puppets I've actually animated — and truth-be-told, the majority of puppets in professional studios — have wire armatures. Frankly, the benefit of being able to create a puppet quickly is usually more important than having one that's perfect.

Besides the armature, I also want puppets that have a very sculpted look. With build-up puppets, you can do a lot with hard body parts made from Super Sculpey or epoxy clays (such as Magic Sculpt, Milliput, or Apoxie). Given the look I want, though, I'm naturally drawn to mold-making and casting puppets in foam latex or silicone. I've had some successful experiments, but am still in working on really learning the skills.

What materials you prefer to use and why?

Every material has a place in the puppet-maker's toolkit. A puppet's head might be made from polymer clay in order to gain more working time while sculpting — whereas the hands and feet might be made of quick-curing epoxy (much stronger) to avoid being broken, since they're so close to high-stress joints. For humanoid puppets I like to use hard parts whenever possible, so that I don't have to fuss with re-sculpting soft clay mid-shot. But, on the other hand, I also like working with clay on its own terms. I think that animating with clay can be like having a 3-dimensional sketchbook... It allows you to improvise and explore ideas in ways that build-up and cast puppets don't. For any kind of artist, I think it's important to make improvisation a regular practice. Make elegant puppets — but also play with shapeless blobs. Ultimately, I think it's good to avoid getting stuck in one set of materials; you should strive to have all of them at your disposal, and know which is right for a particular job.

In your point of view, how does social media and technology influence modern stop-motion animation?

Stop-motion has undergone a technological revolution in the past 15 years. With the advent of frame-grabbing software, animators have the ability to toggle back and forth between frames, making sure that they're getting the shot they want. Before this, animators used tools like surface gages (many still do) — but mostly had to rely on sheer mental focus to keep track of what bits were changing between shots. Subtle stop-motion is still challenging — but far easier now that you can check your work before committing.

The internet and forums such as StopMotionAnimation.com and AnimateClay.com have also played a huge role in stop-motion's renaissance. It used to be extremely difficult to find good information about how to make our specialized puppets. Now there's an active online community where masters and amateurs co-mingle, solving problems and learning from one another. Some of the magic may have been lost in the process of revealing the art form's secrets — but as a result, an art that once seemed on the brink of extinction is prospering again.

I think stop-motion is particularly suited to communal discussion, too. With computer animation, it can be challenging to explain what's going wrong with your software. Stop-motion, by contrast, is all about craft projects. "Show and tell" is much more intuitive when you're working with real, tangible materials like clay and wire and foam.

The web is a godsend for stop-motion animators as people. It's difficult enough to find in-the-flesh communities of animators. When you do, stopmoes are usually a minority. Being able to Google "stop motion" and find a bunch of people doing the same sort of work breaks the isolation — and then allows friendships to form. My most valued circle of stopmo friends is made up of individuals living in Los Angeles, San Diego, New Orleans, Atlanta... While I'm all the way up here in Portland. We keep up with each other via show-and-tell on our blogs, through "hey, have you seen this?" emails, and the background noise of Twitter. We've kept tabs on one another during hurricanes and earthquakes, when there's a medical crisis, or when someone just goes missing for a while. ...But of course, that story of "internet relationships extending into the real world" has been true for many types of online affinity groups, not just our own.

Technologically, the most curious thing to me is seeing stop-motion beginning to become indistinguishable from computer animation. The advent of rapid-prototyping 3D printers means that objects for stop-motion are being created first in the computer, then translated into real sapce. Motion control cameras allow dizzying moves that were the sole purview of CG not long ago. When Coraline came out, the stop-motion community seemed torn about how to feel... On the one hand, the technological accomplishment was unprecedented. On the other, the quirky jerky movement usually associated with our hand-made films seemed to be disappearing.

Since Coraline, rapid prototyping technology has spread rapidly among professional stop-motion studios... And it looks like LAIKA's follow-up to Coraline — titled ParaNorman — will push the limits of technology even further. I have no crystal ball — but it seems like in the near future, most of what CG can do (with the exception of large crowd scenes) will be able to be accomplished in stop-motion with nearly identical results. Then what? ...Frame-by-frame hand-drawn animation has been on the wane for a while — perhaps it will have a resurgence. We crave uniqueness. Just as with stop-motion, what's currently being ignored will soon start to look fresh and new.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: stopmo, writing

March 11, 2011

suffering manager promoted

by gl. at 5:33 pm

sven & i have a writing night in the studio; we take turns bringing prompts. "suffering manager promoted" was the result of 3 slips of paper sven drew from a box, and led to us both writing 10-minute freewriting fictions that cracked us up:

sven:

The suffering manager works at a convenience store. A store which, naturally, specializes in suffering. The suffering manager oversees the employees: irritation, melancholy, bowel-quivering horror, and tear-stained pillows. Irritation is the most reliable worker—always on time, always willing to take a shift. Tear-stained pillows is in charge of furniture in general… Beds that one doesn't get out of in the morning, exotic fainting settees. Melancholy comes and goes on her own time, seemingly ignoring time cards, moping on the floor next to the refrigerated beers' glass door with an unlit cigarette. Bowel-quaking horror cleans up the restroom with a 9-year-old mop and dispenses menthols with a wide-eyed, dilated sense of doom. Suffering manager oversees them all, tries to schedule them so that X can have Valentine's Day off with her boyfriend, Y can attend his grandfather's funeral… And come back with bloodshot eyes, stinking of alcohol. Suffering manager deserves better than this… Dreams of a quiet job in the pharmacy, metering out pills that an assistant patiently explains to the customers. His days of dealing with time cards are numbered, he thinks with relief. Promotion promotion promotion! The letter in the mail though—not what he expected. He's been fired from the Convenience Suffering Mart. The thing about it: he's just not sure how to feel.

gl.

whoo hoo! i finally got promoted to misery manager! i’ve been waiting for this day for ages, ever since i started as the mild angst receptionist so many years ago. i have big plans to move all the way up to the ceo of hopelessness and despair, but i have to take one step at a time. i am going to go home tonight and find myself some company, drink some champagne and complain about how much i hate my job. it’s great to be paid for something i already love to do. sometimes i imagine what it’s like to work for the happy happy happy corporations, the ones that manufacture smiles and good cheer, the ones that require a song and dance from each employee every morning to prove they still belong there. i get chills thinking about how horrible it must be to be so cheerful and delightful. they have to call in sick when they get sad. i even know someone who was fired when they got overwhelmed with depression, and is now much happier working for us. of course, the one thing both companies agree on is that nobody wants to work for ennui, inc. nothing gets done there. moping and listlessness have a very minor marketplace niche. it works for some, but it will never be a big player in the emotional ecosystem. when i go to work tomorrow as the new misery manager, i’m going to call a big departmental meeting to get feedback about what we should be doing to make the world a more miserable place. for instance, i’m really proud of our legislative action team, which is doing great things in the U.S. political arena. i want to find a way to reward them.

posted by gl. | permalink | categories: writing

February 14, 2010

be my valentine

by gl. at 12:01 am

this valentine's day marks the fifth year of the scarlet star studios blog! happy blogiversary!

sven & i attend a free first friday writing group hosted by ibex studios. this month one of the quick 10-minute prompts was to write a letter to something we loved, so here's a letter i wrote to my beloved ebike, rose:

dearest rose:then we wrote a 10-minute story about a date using several words drawn from a bowl:you were not my first love and you will not be my last. you are not even my best loved love, but i want you to know that knowing you has changed my life forever. you are beautiful and curvy, strong and swift. many people comment on your grace and beauty, but few suspect what you are capable of and i love sharing this secret between us. even more, i love flying with you beneath blue skies, when the day is free and the world is wide and my heart is open. i love riding with you in the sunlight, the moonlight and even when the snow twinkles in the streetlights. i feel like a better person when i am with you: strong, brave, lighthearted and ready for adventure.

love,

gl.

i escaped to the bathroom of a new orleans strip club, and if there had been a window i probably would have climbed out of it to escape my date, a judge with a very large gavel -- if you know what i mean. though he was sociable and very, very generous, i finally had to flee from the pounding music and flashing lights and ask myself what the heck i was doing here, anyway. the question answered itself in the form of Mary, who was just leaving the bathroom as i pushed the door open. “watch it, hon!” she said, not unkindly. i did. i couldn’t take my eyes off her. i don’t suppose this is the story we’ll tell our grandchildren about how we met.

[words drawn: new orleans strip club, sociable, generous, present, gavel]

posted by gl. | permalink | categories: miscellany, writing

July 30, 2009

essay: stopmo webcomics

by sven at 10:40 pm

What if you created stopmo clips as if you were producing content for a webcomic?

Imagine: an ongoing series of 10-20 second clips that get published once a week… Some are stand-alone gags -- but others are part of large, dramatic story arcs broken into bite-sized episodes. Keeping a strict update schedule is critical, and somewhat stressful… Yet, the pay-off is a loyal audience that builds watching your show into their personal weekly rituals.

For about the past month, I've been really excited about this idea. Here I'm going into "deep thought" mode to flesh out the details.

1. ROLE MODELS

Amongst stopmoes, there are several popular role models. The Neo-Harryhausians (as I think of them) idolize "Uncle Ray" and yearn for the return of photorealistic stopmo monsters to feature films. Another group takes their inspiration from Tim Burton's Nightmare Before Christmas and Corpse Bride -- as is often apparent from the Gothic/German Expressionist influences in their character/set designs. Yet another group longs to follow in the footsteps of Will Vinton, fondly recalling the heyday of the California Raisins.

Whether the role model is Ray Harryhausen, Tim Burton, or Will Vinton, the career path that most stopmoes fantasize concludes with the publication of a feature-length film. The route to this goal is either a slow accrual of victories in the film festival circuit, ultimately leading to a deal with a big investor -- or the founding of one's own boutique studio, capable of taking on a multi-year project.

Lately, though, I've been looking to a different set of artists for inspiration.

I've become a loyal reader of several webcomics: Jeph Jacques' Questionable Content, Richard Stevens III's Diesel Sweeties, Randall Munroe's XKCD, Rene Ergstrom's Anders Loves Maria, Danielle Corsetto's Girls With Slingshots, to name a few. I've devoured the (live action) webisodes of Felicia Day's The Guild and Joss Whedon's Dr. Horrible's Sing-Along Blog. I've eagerly awaited new webtoon episodes of Amy Winfrey's Making Fiends (and now Squid and Frog) and lost afternoons to Mike Chapman and Craig Zobel's flash cartoon Homestar Runner.

What do these artists' webcomics, webisodes, and webtoons have in common? They're all presenting story worlds in an episodic format, using the internet as their primary distribution media… And what's more, they're all independent artists that publish according to their own time-tables, maintain absolute creative control of their content, and earn a living from their publications.

Sounds appealing! So, while I still admire the works of Ray Harryhausen, Tim Burton, and Will Vinton, I think it is these others that I want to be studying as I devise my potential career path.

2. WEBCOMIC BUSINESS MODEL

Surveying webcomics, webisodes, and webtoons, I think that the clearest business model has emerged among the folks doing comics…

Actually, there are really two business models among webcomics: "fee-to-see" or "free-to-see." With fee-to-see, there's either a tip jar (honor system) -- or you get a free sample and then pay a subscription to get into the archives. With free-to-see, the archives are all available -- profits come from selling ads and selling merchandise. Among the folks I've been reading, fee-to-see has been roundly rejected (e.g. How to Make Webcomics by Kurtz, Straub, Kellett, & Guigar; Jeph Jacques' post titled comics comics comics)…

So I'm identifying the webcomic business model with publishing high-quality free-to-see content that attracts an audience, then selling ads and selling merch to make a profit.

Contrast this with how people in film culture (hope to) make their money. Feature films in the cineplex or at art house theaters are fee-to-see. You have to fill seats in order to make your investment back -- which necessitates a big promotional campaign of posters, TV ads, etc. If you're aiming at placing your film on TV, then it's essentially the broadcaster who's paying the fee-to-see -- or more properly in their case, fee-to-play.

And if you're not at a point in your career where you can get mass-market distributors to buy your content? Well, you can try to win award money in the festival circuit -- but you're pretty much back to selling merch -- your DVDs… Either setting up a table at the festivals, or by word-of-mouth / internet publicity.

Some filmmakers are thinking about how they can further monetize their pet projects by selling non-DVD merch… T-shirts, toys, and stickers derived from their films. However, I believe they're unlikely to create significant revenue streams through these efforts.

Why? It works for the webcomics, right?

Well, see the problem is that most filmmakers' shows are one-offs. The films may make a big splash the first time an audience sees them… But then the film is forgotten by the next day. An integral part of what makes webcomics' merch business feasible is that they're releasing new content daily, weekly, or monthly -- not just every few years. The frequency of release is what allows brand loyalty to develop, which is what really drives purchases.

3. RELEASE SCHEDULE, LENGTH, EPISODIC STRUCTURE

Obviously you can't hope to put out feature-length stopmo films on a weekly basis. If you choose to increase the frequency of your releases, then the nature of your creations must also change.

I want to discuss how three interrelated issues will shape the form of your art: (a) release schedule, (b) length, (c) episodic structure.

Webcomics tend to update either daily or on something like a M-W-Fr schedule. Webtoons can get away with updating monthly; some flash cartoons manage to update weekly.

The longer the wait between new releases, the longer the clips you can create. However, the longer the wait for new releases, the more you lose your audience's attention. So, while there's an impulse to cram as much story as possible into each installment, personally I want to push myself to think in the opposite direction: What is the shortest video clip I can produce that still conveys a meaningful unit of comedy / drama?

Personally, I think that you could get away with publishing only 10-15 seconds of footage per week. If you have dialogue, that's just enough time to have Character A speak, Character B respond, and Character A react.

As an experiment, try taking a standard newspaper comic strip, 3-4 panels long, and read it aloud… 10-15 seconds is my best estimate. …The 3-4 panel comic strip is also a good comparison because each of those panels is the equivalent of a storyboard panel -- in which case, it seems you're looking to create episodes that are about 4 storyboard panels in length.

[Of course, if you want to publish on a monthly schedule -- 4 weeks worth of work -- you could probably get through 16 storyboard panels, and shoot about 60 seconds worth of footage.]

Won't working in such tiny segments cripple your ability to tell a story? …Not necessarily.

Once you commit to putting on a once-a-week show, you realize that there are two categories of episode: stand-alones, and serials. For stand-alones, think of "Garfield." When you read one episode of Garfield, you generally don't need to know anything about what came before, and aren't left wondering about what will come after. For serials, think of "Dick Tracy" or the old "Buck Rogers" cartoons. There's a storyline that carries on from week to week, which has continuity.

So here's something I'm interested in experimenting with… Take a graphic novel -- like Maus, Watchmen, or Persepolis -- and try to chop it down into smaller segments. Can you take a long-form script and figure out how to present it in three or four lines of dialogue at a time?

It seems likely that through the process of presenting stories in such short segments, the way in which you communicate will change. But this is nothing new… Look at how storytelling for television adapted to fit the needs of the medium: instead of presenting entertainment for a continuous hour, there are several mini-climaxes to help the audience bridge the commercial breaks. In my opinion, storytelling always adapts itself to the medium.

Stopmoes are familiar with feature-length films and short films… What I'm discussing here would perhaps best be termed "micro" length. "Epic" feature-length films are generally felt to be superior to short films, due to scope and grandeur… But I am of the opinion that a long-running serial of micro-length films could equal the emotional weight of a feature -- and even has some advantages over it, production-wise.

First off, when I think about the stories that I personally love most, they're all serials. Star Trek, Battlestar Galactica, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, Firefly, The X-Files… Frankly, a 13 or 26 hour season of TV shows is able to give me a richer world than a 90-120 minute film -- no matter how big the explosions!

Secondly, from the perspective of being an indie filmmaker, I find the long breaks between having completed films to show extremely demoralizing. The more often I'm able to put out a film, the more legitimate I feel as an artist -- and the less isolated I feel, off in my story universe. The sense of pride in completing small films frequently, and being able to show them to friends, family, and the world -- I find these aspects of micro-length work very attractive.

4. LIVE SHOW ETHOS & PRACTICALITIES OF RUNNING A WEEKLY SHOW

When you spend years working on a single film, the deadline for completion ceases to matter very much. You want to make the film exactly right, because you take pride in your craftsmanship. The final product of your effort is a DVD, an object, a unit of property to sell.

When you work on a weekly show, I believe the experience is a lot more like doing live theater. You've told everyone that there will be a show Friday night -- so ready or not, when the curtain rises "the show must go on." If you have to cut corners or improvise, you do what you have to do… The fact that you get up on the stage try to be entertaining is more important than whether or not you feel ready. And if you flop? Well, there's always next week.

It seems to me that if you commit to putting on a weekly stopmo show, the following guidelines will be helpful:

- Use what you've already got. Fabrication is time-expensive, and time is what you don't have!

- If you have a set or a character, re-use it multiple times. There are plenty of story possibilities in those elements -- exhaust them.

- Keep a library of sets and puppets. Once you have an asset, don't throw it away!

- New sets and puppets will be added to the library piecemeal. You'll be very lucky if you are able to add one new puppet or one new set each week. To do so adds at least a full day's labor.

- Plan puppets/sets to be multi-use. Until you have the resources to start off an ongoing show with multiple elements, try to make elements that could be used together in different ways. Scale and aesthetic play into this thought process.

Think about the Muppet Show as an example. Once you have the "Pigs in Space" set and puppets, you can do a skit that uses these assets once every episode. The audience doesn't get bored of such recycling -- rather, it becomes something familiar to look forward to.

I mentioned earlier that there are two types of segment that you can do using the episodic structure: stand-alones and serials. It strikes me that so long as you have a weekly schedule, there's no reason why you have to choose one or the other. You can start off doing stand-alone clips, then sprinkle in installments of larger story arcs as you finish fabricating the necessary sets and puppets. Recycling old puppets and sets in new skits buys you more time to fabricate bigger worlds -- so there's no dead time in the performance schedule while you're preparing something more ambitious.

5. FILM CULTURE VS. COMIC CULTURE

It seems to me that most stopmoes want to be a part of film culture. By "film culture," I mean that the community of filmmakers and film-lovers meet together annually in gatherings across the country known as film festivals. Often there's not as much interaction between the filmmakers and audience members as we might like -- but often enough there are panel discussions, vendor areas, and good conversations in the lobby. Like Brigadoon, the magic city that appears only for a day once each year, the film culture manifests through such events.

Webcomic artists, on the other hand, have a separate culture. Webcomic and print-comic artists alike gather at comic conventions… The biggest and most famous of which is the San Diego Comic-Con. I ask myself: could a stopmo doing a weekly micro-length show fit in in the vendor areas of such cons? My answer: heck, yeah!

Things that a weekly stopmo show has in common with your typical webcomic: a cast of fictional characters, a primarily visual medium, episodic story structure, geek appeal… While not without some controversy, notice how the San Diego Comic-Con has grown to encompass films and toys as much (or more than) comics. It seems that the con is really about fictional universes… And the characters leap effortlessly between media -- from novels to comicbooks to films to toys.

The only firm difference I find between webcomics and stopmo webtoons is that you can't read a film -- you have to watch it. Technologically, you need a player of some sort. But even so, you could make an academically sound argument that stopmo is just another form of "sequential art" (to use Scott McCloud's term)… You're just viewing animated comics at 24 panels per second!

So: I think that a stopmoe could embrace the identity of "webcomic" or "webtoonist" and fit in just fine in the comic convention culture… But would film culture have them back again if they did?

Micro-length films might be compiled into a longer film to show at festivals… But I have my doubts about how well the compilation would flow. If the film clips weren't made to be shown as a continuous series, translating them for the big screen is likely to be clumsy.

What's more, many of the prestigious film festivals do not accept submissions that have been shown in public previously -- which would automatically disqualify stopmo webcomics/webtoons. Yet, if you were willing to sacrifice the competitive fests, you could still take your works to other fests… Which would then allow you to sell DVDs in the vendor's area, if nothing else.

PARTING THOUGHTS: A VIABLE ALTERNATIVE

The stopmoe community has wrestled with the question of how much of one's content should go online. One side in the debate has argued forcefully that it's a mistake to just give your work away online, without any hope of making back your investment. Particularly if you think you can get into film fests, then you should keep your work offline and keep it secret.

Having explored the webcomic model of publishing a fair bit now, I think that there is a way to make a fair profit from putting your films online -- but the nature of the films has to change considerably for the magic to work. What's important is to post your content with maximum frequency… Which in turn necessitates micro-length, and then propels you toward telling stories using episodic structure.

I'm not personally at a point where I'm ready to commit to doing a weekly show -- but I think it's very exciting to identify a viable alternative to the filmmaking role models and business models we're familiar with.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: stopmo, writing

June 26, 2009

wiping the slate clean

by gl. at 6:15 pm

it's been a very long time since i've posted, and it looks to me like if i wait for the perfect time to give each item the post it deserves, i will never post again.

during the holidays, at the masarie curry party, marta said i changed her life: she attended a collage night once and makes one every day now. it's not often you get to hear something so dramatic or sincere!

but it's been hard because a bunch of awkward things happened at once. my focus has shifted to include arts organizations. i've been spending a surprising amount of time & energy supporting medical causes. my own art has re-embraced theatre. a lot of people have died (including lane, my mom & sven's grandfather). my primary art support group collapsed. my photo routine is broken. the economy shook us. in short, things are in flux.

since sven & i are about to go on a long summer trip, i'd like to tie up some loose ends so when i return, i can start with a clean slate: i'm still searching for the next surge of momentum but i can't move forward if i'm still looking back. so here are some things that have happened over the last year i'm not going to write much about but that are worth mentioning & recording:

events: shu-ju in the rare books room, gems of small press show, red bat & loaded hips show at iprc, white bird dance series, open studios (cirocco moody's raven), shawn demarest's shows, trillium holiday show, handmade nw, little things show, coraline premiere, a puppetlove show, apollo, how to disappear completely, hidden portland book launch, crazy enough, inviting desire w/ bridget, an afternoon on dayna's boat "rapture." plus, dayna went to italy & brought back treats: a fish placemat from volterra in in the cinque terre, yellow italian paper (used to wrap purchaes, in art, as placemats, etc.), a menu with cool image, favorite yogurt jar, a sugar packet, a piece of broken window from abandoned house in tuscany(!) wrapped in italian newspaper, red & white rocks from cinque terre, beach glass from the amalfi coast, a bookmark from assisi, and a metal botanical tag from flea market. then ann gave me a subscription to “where women create” magazine, which is like a “lifestyles of the rich & creative."

teaching: i had a great time teaching gocco at the iprc until the iprc could no longer offer them due to the shortage of supplies. (however, i still provide private gocco lessons, like the one i did with dot.) so i've been teaching creative business classes at the iprc, the library & trillium/scrap. that may come to an end soon, too. i've been re-offering workshops at the studio without being responsible for promotion & registration.

classes: when i first decided i wanted to dip my toe back into the theatre waters, i took a theatre/coaching class: it was a really rocky way to start because she did not believe in encouraging students. so i was both relieved & sad to leave. i had better luck at the 100th monkey's "ninja sewing" series (where i learned about threading, knotting, warp/weft, running stitch, gathering stitch, back stitch, buttons, hem stitch, blanket stitch, cross stitch, whipstitch, chain stitch, split stitch, french knots) and have been happy to be able to make and repair very simple things.

art: "where the sidewalk ends" photo series, "5 reasons" book, comparing down to earth "smoke rings" a year later, "writing our bellies full" reading, fidelio, last big gocco supply order, cast as an extra in TNT's "leverage" (so was trixie!), opsfest, dayna's art buddy invitational (my buddy, sven's buddy).

at the little things show, i picked up a prayer flag by jennifer mercedes because of its title: "a prayer for an inspiring future." yes, please. see you soon.

[gl. as The Lyon in A Midsommer Nights Dreame]

posted by gl. | permalink | categories: administrivia, classes & workshops, exhibits & events, miscellany, other art, printing, trixie, writing

April 20, 2009

parenting your brainchild

by sven at 11:59 pm

When you produce a piece of art, it could be called your "brainchild." I think it's a really rich metaphor… So here is my exploration of the implications.

conception, pregnancy, birth… and beyond

Lots of struggling artists ask "where do you get your ideas?" It's sort of like they're dating… And they think all the hot muses are already taken. But maybe if you just go to the right bar… What kind of pick-up lines work on ancient Greek chicks?

Where do ideas come from? Well, when an artist and a muse love each other very much… Generally you start with juxtaposition (innuendo intended)… And then things grow from there.

After conception, there's frequently a "gestational" period where you walk around with this thing inside you quietly growing…

Until ultimately you're ready, and go into labor. It can be painful and prolonged -- but seeing a newborn brainchild is a miraculous experience. I made this!

And that's generally where the metaphor ends.

But wait! Don't just leave the newborn in the crib and walk away from it! Its life has only begun!

growing, maturity, finding a career

If you just put your brainchild into a drawer, it dies. A work of art lives and grows by finding an ever-expanding audience.

When a brainchild is born, the first thing to do is call your family… That is, your circle of peers who have a shared love of the art form. Let them know that something new has come into the world, let them come over to your house to meet the thing.

At first, you only introduce your brainchild to the people you trust the most. But still, when company comes over, you put some clothes on your offspring: formatting. If it's a film, burn a DVD. If it's a play or a short story, put the text into a zine-style binding. A stack of papers without a cover, or a video that doesn't have a case… Is naked. It's unseemly.

Showing the brainchild to your peers is its infancy. In its childhood, reach out to a wider audience: email friends who you're less close to, make it available for sale on your website, make it available through local stores. Let the art get to meet people outside of your immediate family.

In the project's adolescence, send it to finishing school: use print-on-demand services to create a book that's perfect-bound or a dvd that's professionally printed and available on amazon.com via createspace or through indieflix.

You've done all that you can to introduce your child to the world and make it socially presentable… Now it's time to send it to college: playwriting contests, film festivals, the like. Places where the work will get tested and graded. Why? Not because the grades mean anything in themselves. It really doesn't matter how you do in school -- what's important is getting recommendation letters.

You can show your brainchild to everyone you know, and then do as much promotion as you know how to do… But ultimately what's going to launch your book or film on a successful career is how it gets reviewed. See, most of us don't just randomly pick up a book or go to a film we've never heard of -- we check things out because someone we trust (who's a fanatic for the art form) thinks they've found a real gem. There's so much crap out there -- it's a valuable service they provide!

And so this is the career of your artwork: to be seen by as many people as possible. It wants to be seen -- your job as a supportive parent is to give it as many opportunities as possible.

Maybe your artwork will even find a high profile employer: a distributor that adds your film to their product line, a theater that produces your play, a publishing house buys the rights for your book. If that happens, then congratulations!

But remember: you don't have to be a doctor or lawyer to have a worthwhile career. Your art may have a very humble career, only reaching a dozen or so people… Do what you can to help it go as far as it can, reach its full potential, even so.

To summarize: A brainchild grows as you put the naked work into increasingly pleasing physical formats. It reaches maturity when it finds its maximal audience. Its career is the length of time that it's alive and active in the world, meeting new people.

the decision to be a parent

Few parents -- I mean artists -- really belabor the decision to have brainchildren. It's just in our nature to create/procreate.

But once the brainchild has left your body… [insert image of Athena bursting from Zeus' forehead] …Then the real challenge begins. It is in our artistic DNA to give birth -- but raising a brainchild takes thought, courage, and perseverance.

Let's take a step backward a moment and consider the subconscious reasons why people want to have brainchildren.

- Money. You like making art -- what concerns you most is how to make a living at it. How are you going to get a job in the field? What kind of art do consumers want to buy right now? How can you get a meeting with the publishing giants who'll give you a contract?

- Fame. Your name is a brand. How do you increase brand recognition? Can the judges see that your art is the best? What's been written about you? Are you known yet?

- Immortality. A variation on fame… Is your work perfect yet? Is it a masterpiece that will be remembered for generations? No? Then maybe you're not ready to share your work with anyone.

- Self-expression. Who cares what anyone else thinks about your work? It is the raw stuff of your heart and soul. If people like it… Then you'll feel understood at last. But if they don't? Ultimately all that really matters is your personal experience, the process of the making. It's about self-love.

I think most artists have some combination of these values in their heads. And I don't mean to say such goals are bad or wrong… Even when taken to extremes. (Personally, I know that my weakness tends to be for the immortality fantasy.)

But here's what I notice about these options… It feels like the brainchild is getting exploited. I want my child to make a million dollars so I'll be rich. I want it to be famous so I'll be famous. I want it to be remembered so I'll be remembered. I'm a bit alienated by the world, and so want the art to stare back at me and say "I understand."

Is that fair to the art?

parent-child boundaries

If we hold on to the metaphor of art piece as child, then these desires all sound like unhealthy relationships. The alternative? Boundaries. To see the art as a separate person. To do what you can to help it grow up strong and true -- but know that ultimately it is its own person.

Translation: Let go of your brainchild and let it leave the nest. It may not be perfect, or an ideal money-maker, or reflect well upon your reputation… But it should have the opportunity to go out into the world and meet people nonetheless.

But why would you let your brainchild leave the house dressed like that? Two reasons: unconditional love, and the fact that we may be poor judges of our own work.

Your art may be lumpy, awkward, misshapen. Even so, don't abuse it (and thus yourself) by calling it names or casting it out. Do everything you can to help it. Take it to the orthodontist and get some braces if you have to. Help it grow by giving it attention and care. And then, when you've done all you can do and have to call it finished… Show it to your peers without apology. Stand behind your work, even if it's an ugly child.

Frankly, it's probably not nearly as ugly as you think, anyway. In general, I think we're fairly poor judges of our own work -- at least in terms of guessing what other people are going to like. The piece you think is awesome doesn't seem to connect with the audience… But the piece you felt ho-hum about turns out to be your smash-hit. It's humbling… So embrace the humbleness.

be fruitful and multiply

One bit of unsolicited advice for potential brainparents: have lots of children. Big families are a good thing.

When you have an only-brainchild -- the masterpiece -- there can be such pressure on it to live up to all your expectations. The brainchild gets lonely… And when you get into fights with it, there's no one else around to help break the tension.

When you birth a couple of children in rapid succession, you learn to mellow out pretty quickly. Whereas you wanted to do everything perfectly with the firstborn, and were a strict parent -- as more come along, you're content just as long as no one breaks a bone. You'll be happier both with yourself and with the kids when you've gotten over that initial "perfect parent" thing.

And, you know what? I suspect that you're more likely to become rich, famous, remembered, and self-loving when you're known for your whole family -- your body of work -- rather than for your one, solitary honor student.

the adoption option

Even if you're able to view your artwork as a separate entity from yourself, there's been an assumption throughout this exploration that what the brainchild is made out of is your own personal Artist DNA. The art is a little piece of your soul that's been pinched off and reshaped into… Adam.

Well, lately I've been exploring what it feels like to instead be a foster parent. That is, rather than looking for the divine spark deep inside of myself, I'm searching the streets looking for orphans who need a good home and some love.

Perhaps the metaphor's become opaque; let me drop pretenses.

What I'm doing lately is using "intuitive collages" as the foundation for image and story generation. I collect huge numbers of images from magazines or online. I select whatever appeals to me in the heat of the moment, without trying to impose meaning. Then I play with juxtapositions until something new starts to appear. When I glimpse some exciting combination, I develop it through writing and then begin work in my final medium (drawing, sculpting, writing fiction, etc.).

The remarkable thing about this process is that even though it doesn't draw directly from my imagination, my imagination is nonetheless engaged and responding. So, while the germinal idea -- the seed for the brainchild -- doesn't come from my own DNA, through the process of developing the material it comes to feel very much my own. Like a child I've adopted.

a finder and a helper

Perhaps artificial insemination is an even better metaphor there? Maybe so.

The thing I like about describing these ideas as fostered or adopted children is that it helps me give up possessive ownership.

I recognize an idea that wants to be born because it has an organic form to it. I love that sense of finding. It's as if the idea has always existed -- it's my job to play midwife for it, then to help it find its way out into the world. But while I may have spotted the idea first, in reality anyone could have discovered it and put their own spin on it. The idea belongs to itself. I'm a finder and a helper.

So, ultimately, this is a way of looking at art that has an altruistic spin to it. No, it's not the audience that you're doing a favor -- it's the idea itself that wants to be born and to have a life. A pleasant anthropomophization.

All those selfish reasons for doing art…? Absolutely, I still get a hit of satisfaction when my work succeeds in those ways. But there's something about this caring detachment that seems to keep me in the right headspace -- dutifully doing the work that needs to get done.

It's joyful.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: writing

April 14, 2009

reading frenzy sells "buried piano"

by sven at 7:00 am

My booklet, "The Buried Piano And Other Plays," is now being sold at Reading Frenzy. It costs $3 and will be available for at least the next 3 months.

Reading Frenzy is located at 921 SW Oak St., Portland OR, 97205. It's open daily from 12-6. The store's mission:

"Reading Frenzy -- An Independent Press Emporium -- is a multifaceted hybrid project: part book, zine and comic shop, part art gallery, part community hub and event space. Founded in 1994, we are devoted to supporting, promoting and disseminating independent and alternative media and culture, with a focus on the arts, politics and current events, d.i.y. culture, comics, girl's stuff, queer notions, and quality smut. We stock thousands of hard to find titles from around the country, host dozens of literary and art events every year, and support local community organizations who share our goals of fostering freedom of speech, information and creative expression."

Last week I offered free copies to our blog readers… That offer still stands -- but you only have until Friday to speak up.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: writing

April 6, 2009

freebie: the buried piano & other plays

by sven at 7:00 am

Freebie! For a limited time, I'll send anyone reading this blog a copy of my new booklet, The Buried Piano & Other Plays. All you have to do is email your snail-mail address to sven (AT) scarletstarstudios (DOT) com. (Even if I already have your address, please.)

The booklet is 34 pages long, and contains four plays:

- The Buried Piano

Gina's parents are powerful patrons of the arts… But when her "edgy" boyfriend gets kicked out of the party, she realizes she can't tolerate playing the good daughter anymore.

- Re-Imagining The Bomb

General McGraw asks a group of artists to help improve nuclear weapons' public image… And gets more than he bargained for.

- Hell's Merry-Go-Round

A mysterious figure offers to grant 10-year-old Becky a life of adventure… Unfortunately, she gets her wish.

- The Astronaut & The Nude

A man who seeks the giant squid and who rockets into outer space… A woman who dreams she's shrinking to the size of a pea -- and growing larger than the world… How will their marriage survive?

posted by sven | permalink | categories: writing

April 2, 2009

the appeal of comedy and horror

by sven at 7:00 am

[An essay written to some email friends on 3/27.]

I think there's a strong relationship between horror and comedy.

Both are intentionally visceral experiences. At a horror film, you're supposed to feel anxious, revulsion, and startled in your body. When you go to see a stand-up comic, your body is supposed to convulse in laughter.

Physical experiences while you're sitting in safety? Neat trick! And since it's perfectly safe, it almost doesn't matter what kind of physical experience you're getting… They're all interesting at some level.

Comedy and horror also both deal with taboos. And for that reason, both have a sort of fascination because it feels like they reveal Truths that are denied to us in everyday life. We're not supposed to talk about mortality, or that each of us is a fragile being walking around filled with intestines, blood, and gore. ["Not supposed to" because it's upsetting, and being upset interferes with the necessary agendas of daily living.]

Comedy often talks about sex, race, religion… Things that we have a hard time talking about as a society because there are real political tensions there. But the Shakespearian fool and the Native American clown and the social outcasts brought into the center of town for Carnival are allowed to say outrageous things -- under the guise of entertainment -- but also with this understanding that the role allows taboo observations to get heard. I hear comediennes like Sarah Silverman and Margaret Cho being praised for doing comedy in this tradition.

So: horror and comedy -- visceral and truthy.

But also traumatic and addictive.

There's a story I heard once about the Cambodian killing fields; how someone witnessed a group of teenaged boy-soldiers performing executions by bringing baseball bats down on captives' heads. They were laughing as they did it. From how I understood the story, though, this wasn't pleasurable laughter; it was more like the nervous laughter of trauma.

There's a school of psychology -- Re-Evaluation Counseling -- which has not been rigorously tested, incidentally -- that says laughter is psychological distress leaving the body. I think sometimes this is true, but not always. If you look at chimpanzees, they laugh when they're being tickled; but there is also a laughing, toothy smile that is a sign of fear and aggression -- beware! It seems to me that sometimes laughter trickles out as a coping mechanism when a person is absorbing a painful experience, and there's just no other way to deal.

"Sex and violence" are often called "puerile" interests. People often don't realize that the word "puerile" stems from the Latin, "puer," meaning "boy" -- it's a synonym for "childish." I think sex and violence ARE childish interests… In the sense that children have every reason to be interested in procreation, physical pleasure, the level of violence that human beings are capable of doing, and what sort of personal armor you have to wear in order to be ready to face it.

This is very existential stuff, all about what it means to be alive in the world. You're not born knowing it; you have to learn it. And anyone who stands in the way of your getting this information, prevents you from accessing the most vital information for living your life. …Is there a Santa Claus? Think about it -- the answer to that question is going to have a phenomenal bearing on your sense of reality. …Are there psycho-killers afoot? Same thing.

Violence is a sort of truth. Yes, there are murderers, rapists, child abusers, and war in this world. Truth doesn't always "set you free" -- sometimes it weighs you down. But it's necessary. And so, when people condemn how violence desensitizes you, I think they're only seeing half the picture. It's unfortunate to lose one's emotional sensitivity through seeing violence. That's a part of what trauma does: it deadens your vulnerability. But if in fact you are living in a community where you are not physically safe, then wearing some emotional armor is actually a vital thing. Carefree children who pick flowers for the Easter Bunny cannot exist in a neighborhood torn by gang violence.

A long way of saying: there's value in understanding violence, including through portrayal in fiction -- but the cost is emotional sensitivity. Poetically, it's sort of like how a guitarist builds up calluses. If you want to play in the world, being soft isn't always functional.

Horror and comedy are visceral experiences… Adrenalin, endorphins, and the like are internally produced drugs. I can understand the appeal of bungee jumping and other "extreme" sports. Once, I took the opportunity to go sky diving along with a large group of friends. At the end of the day, my nerves were singing. Marathon runners, similarly, often talk about the ecstasy of endorphins when they break past the hard part and get into their "zone."

Well, similar positive reinforcement also happens at a less extreme level. Slot machines in Las Vegas are a good example. There's a heightened sense of expectation when you pull the lever; and when you receive a pay-out, that's a positive reward. I'll never forget, as a child, seeing slot-jockies whose fingers had turned silver from handling so many nickels.

So, that's Behaviorism for you: click a button, get a reward, repeat. Horror shocks, laughter, orgasms, slot machine pay-outs, video game kills, and web surfing can all establish patterns that are difficult to moderate through will power alone. It doesn't matter than you really want to get down to work for the day; if you click the mouse again, you'll get the pleasure of seeing another blog. It doesn't matter that the comedy show you're watching is vulgar; if you stick around, the shock value alone can prompt the visceral "reward" of laughter.

I'd like to also point out that Behaviorism effects art producers as well as consumers. If you watch some comedians, such as Jerry Lewis and Jim Carrey, it won't be long until you spot a certain desperation in their eyes. They come out on stage and there's a powerful visceral thrill of stepping into the spotlight… But then they're looking for the laugh. It's their hit of heroin. Certain individuals don't perform purely out of altruism or capitalism -- when the audience laughs, that positive attention feeds them in a way that they can't live without.

Stopmoes… Well, one of the reasons I like stop-motion better than CG is because every five minutes, when I snap the camera shutter, I get a little hit of "Ah! Progress!" Snapping frames for an animated film supposedly takes "patience" -- but in another way, we get our pay-offs much more rapidly than the slot jockey.

So… Horror and comedy: visceral and truthy -- also traumatic and addictive.

The last thing I'd like to comment on is cultural drift.

Over the years, it seems like horror films get more gruesome (compare "Saw" to "Psycho") and comedy gets more vulgar/edgy (compare "Something About Mary" to "The Wacky Professor"). I don't think this should be surprising. Who goes through the trouble of creating horror and comedy? Enthusiasts. People who've seen it all before. Of course there's going to be an urge to go just a little bit farther, to try to do something that hasn't been seen under the sun yet.

Does new comedy/horror lack the subtlety or "restraint" of previous works? Maybe. But perhaps that's unavoidable. Jaded critics of film, stage, literature, art, philosophy -- whatever -- will tell you that there's nothing new under the sun. Maybe it is possible to exhaust the possibilities of creativity. What then? Stop making art? No, you keep trying to do something new and different -- as difficult/impossible as that may be.

As time goes by, there's likely to be specialization, homogenization, and confusion. There used to just be CG animators… Now, to be a professional, you have to specialize in modeling, texturing, character animation, match-moving, and the like. What was once being invented in the garages of eccentrics generalists has now become an institution that insists on specialization…

With institution comes pedagogy. I look at books about how to write movie scripts, and I realize that these authors are all reading the same books. Everyone is responding to the same "big ideas" of the past 10-15 years. It seems that if I want to find new and original concepts, I actually have to go backwards in time… Because some of the geniuses who invented literary theory, cinematography, animation principles etc. -- have been more or less forgotten. Often I find more truth in the flawed writings of people who invented an art form than in the books of contemporaries operating in an echo-chamber.

So, even though at the beginning of the 20th century, we may have the benefit of 100 years of predecessors (in the art forms revolving around cinema), the intent with which people set out to make art often seems quite confused. It's harder to take in "the big picture"… As an artist, I discover something that I like -- and now more than ever it's possible to get stuck in a ghetto with people who like the same things I do… Referencing nothing but what's already been done in this tiny-yet-densely-packed area.

It's the blessing and curse of the Internet Age: maybe there's nothing left but niches.

posted by sven | permalink | categories: writing

March 26, 2009

writing 10-minute plays for stopmo

by sven at 11:27 am

[An essay I wrote to some friends on 3/11.]

Most people agree that the most important aspect of a film is the story. If the story doesn't work, the film doesn't work. So for the past 15 months I've been studying the construction of story.

Before I go any farther… I'd just like to emphasize that dramatic stories are not the only legitimate type of film. For example, some films provide an experience that is primarily aesthetic… If there are characters at all, they're often anonymous, enigmatic, silent; there may be no discernible conflict or climax; but at the end of the film you wind up feeling like you glimpsed something beautiful, nonetheless. Traditional stories with understandable characters, dramatic conflicts, beginnings, middles, and ends, tend to be most popular -- and not without cause… But even though I neglect to discuss other species of filmic experience here, please don't think I'm putting them down!

Back to topic… My research on story has encompassed three art forms: film, literature, and theater. Research tends to start broad; then, as you clarify exactly what it is that you want to know, your scope narrows. So it has been for me…

1. LONG-FORM VS. SHORT-FORM

Film, literature, and theater each have strong internal divisions between long-form and short-form works. In film, there are "feature length" films and "shorts." In literature there are "novels" and "short stories." In theater there are full-length "plays" and there are "one-acts."

The construction of a long-form work in any medium is significantly different from that of a short-form work. Yet, I find it very interesting that how-to books about how to write short films, short stories, and one acts are quite rare. The vast majority of how-to books deal only with long-form works. Some books -- much to my irritation -- even promise to deal with short-form, but then just rehash long-form principles. [E.g. "Writing The Short Story" by Jack M. Bickham.]

At this point in time, I've narrowed my research to focus only on short-form fiction. For literature, I'm reading the monthly magazine, "Fantasy & Science Fiction." For animation, I've been studying Mike Judge & Don Hertzfeldt's The Animation Show anthologies and Acme Filmworks' "The Animation Show of Shows" series (Animation World Network store ). For plays, I've been reading the annual The Best Ten-Minute Plays series, edited by Lawrence Harbison.

A word of caution, though. It seems that the people who care most about the underlying principles of story are those who work in long-form. My sense is that it's just a lot harder to successfully produce long-form work without a strong understanding of structure -- so long-form folks have been forced to develop better theory.

Top picks for long-form how-to books… Screenplays: Story by Robert McKee. Literature: Techniques of the Selling Writer by Dwight V. Swain -- runner up The Art of Fiction by John Gardner. Playwriting: The Playwright's Process by Buzz McLaughlin -- runner up The Dramatist's Toolkit by Jeffrey Sweet.

Note: In my experience so far, screenwriters have the weakest understanding of story. It feels to me like the field is infected with a number of gimick-based methodologies that may in fact help you to doctor an existing script -- but that are rotten foundations on which to build your basic understanding of story. Beware!

2. WHAT'S MOST USEFUL TO STOPMOES: FILM, LITERATURE, OR PLAYS?

I've become convinced that the most useful medium for stopmoes to study is theater. Why?

The biggest reason: limited number of sets. With films, you can easily have the story take place in 80-150 locations. It's no big deal, because typically existing locations can be used. You don't have to build everything from scratch, as with plays and with stopmo. Plays tend to have just 1-3 major sets… Or perhaps merely imply their sets by using "black box" technique. Given the time entailed in building miniature props and sets, stopmoes have to be conservative.

Another reason: only concrete actions are allowed. With literature, you can do amazing things with adjectives and metaphors: e.g. "the wounded leaf somersaulted down to the ground like a football player who's just been shot in the ankle." There's no easy way to translate this poetry to the screen.

Similarly, you can get away with a good deal more inner monologue in literature… Granted, with film and theater you can do voice-overs or break the fourth-wall (having actors talk directly to the audience)… But generally it is ill-advised to do so, because you're violating the principle of "show, don't tell."

Now, theater is not a perfect model for stopmoes. There's a heavy emphasis on dialogue in theater… Remember that most audience members are going to be 50+ feet away from the actors and only get to see the action from one vantage point. Stopmoes would be well-advised to exploit our ability to provide cinematic close-ups and different camera angles. We should also try to convey information through purely visual means wherever possible -- both because we're working in a more visual medium, and because of how laborious it is to do lipsync.

Despite these caveats, it seems to me that the beginning assumptions of a playwright are most like those of someone writing for stopmo: don't use too many sets or characters, and tell the story purely through observable actions and dialogue.

3. 10-MINUTE PLAYS: SCALE

There is a genre in theater called the "10-minute play." It's been around since the early 70s. There are a number of national competitions, which have subsequently resulted in several book anthologies. "One acts" can easily run a half-hour long -- so 10-minute plays are generally an even shorter form. For most purposes, one page of dialogue is equated to one minute of stage time (cold reading format, not the format you see published in books). Thus, ten minutes = ten pages.

It seems to me that 10 minutes is about as much as most independent, amateur stopmo filmmakers should shoot for in their projects. Consider the following estimates…

Aardman films expects 4 seconds of finished animation per day from their animators. If you work backwards, you can see that the way they arrived at this benchmark was by allowing animators 5 minutes per shot, shooting at 24fps, over the course of an 8-hour work day. Now, if you shoot at 12fps and are maybe a little looser with your poses, you might be able to get 10 seconds per day -- presuming you can put in 8 hours. Working full-time, then you could accomplish roughly one minute of film per week. Ten minutes of film = ten weeks. Basically a quarter year (13 weeks)… Though mind you, that's not counting puppet and set fabrication, lip sync analysis, and the actual scriptwriting.

Still, a ten-minute film in a quarter year sounds excellent. Can't work full time? If you can do 10 hours each weekend, you can still get the project done by year end. Thus, 10-minute plays are a pretty good match for stopmo animators in terms of scale.

4. 10-MINUTE PLAYS: AESTHETIC

Remember Sturgeon's Law: "ninety percent of everything is crap." I've found this to be very much true even in the annual "The Best Ten-Minute Plays" series.

But actually, this is part of what attracted me to the series. I don't want to read an anthology of the best 10-minute plays ever, with all the crap taken out… I want a sense of who the "competition" is right now. I want to know about the overall quality of contemporary playwrights working in this form -- not be bedazzled by the best of the best, whom I have little hope of ever rivaling. I want to learn from failures and triumphs in roughly equal measure.

The "Best Ten-Minute Plays" series I've been reading is also interesting because for each year (since 2004), two books are put out: one for "2 actors," one for "3 or more actors." In my opinion, the plays with 3+ actors tend to be better. Having 3+ characters seems to set up conflict more easily, and prompts more interesting scenarios. Plays with two random strangers who start spouting observations about one another out of the blue -- well, I find them pretty intolerable.

So, suppose you were to take the best of the 10-minute plays and try to do them in stopmo… Would it work?

I've been worrying about this. Part of the unique charm of stopmo is that you can do things that are unrealistic. You can use fantasy monsters, purple characters with ridiculously proportioned anatomy, cartoony physics, etc. I don't want to completely abandon such stuff.

It's not impossible to write some of these things into stage plays, though. As for character design, think about the absurd costumes that Julie Taymor used in "Fool's Fire" -- or the giant puppets she employed in "The Lion King" or "Grendel." Most 10-minute plays are written with black box sets in mind; brevity means that you're probably not going to make a big investment in sets & props. But just because it's uncommon, doesn't mean there's any reason why the 10-minute format inherently prohibits such things.

The thought experiment that finally resolved this question for me: What if I cast one of the 10-minute plays I've written with characters from "Coraline"? I have a play I've written titled "The Buried Piano." Suppose Coraline played "Gina", Coraline's Dad played "Howard", Coraline's mother played "Ellie", and Ms. Forcible played "Ursula"…

Would it work? YES! It's a particular sort of stopmo film -- one that emphasizes character acting -- but that's an aesthetic that's already been established in the world of stop-motion films.

5. WRITING FOR 10-MINUTE PLAYS

This is a topic for a much longer essay -- but I want to at least touch on what I've been learning about playwriting through doing assignments for my "Dramatist's Toolbox" class, taught by Matt Zrebski.

Central Spectacle

Like Jose Rivera, "everything that I write comes from some kind of image." (The Art & Craft of Playwriting, by Jeffrey Hatcher, p.196) I seem to start from "spectacle" -- some image that excites my imagination. Maybe it can be shown on stage, or maybe the actors put it into my head via dialogue… The head of Orpheus kept in a box. A taxidermied whale hanging from the ceiling of a dance club. A buried piano. A nuclear bomb that's been painted with murals.